In December 2006, Warden Randall Bryant visited Angel Diaz at his cell in the death house. Diaz had a week to go before his execution, and Bryant needed to make sure he was ready to die. The warden had been running the Florida State Prison, about an hour from Jacksonville, for less than a year, but he had already coordinated and witnessed three lethal injections. He was responsible for every detail, from picking the members of the execution team to observing the inmate’s last breaths. He vetted the process until he considered it assembly-line efficient.

Part of that efficiency rested on his developing a relationship with the condemned man. Bryant patiently explained to Diaz the mechanics of how the state would kill him. The warden believed that such heart-to-hearts helped him assess the inmate’s mental state and lessened the chance of a fuss when the time came.

Diaz didn’t fuss, Bryant later testified at a court hearing. On the day of his execution for the murder of a topless-bar manager, Diaz declined the offer of a Valium to calm his nerves. An hour before the lethal injection, the warden had a translator read to Diaz, in Spanish, the death warrant signed by Florida Gov. Jeb Bush (R).

Diaz changed into his regulation white shirt and pants. Bryant noticed that Diaz shivered as he took off his T-shirt, and the warden told Diaz he could keep wearing it if he was cold. For this, the two didn’t need an interpreter. Bryant then asked Diaz if he wanted more time to pray. Diaz said no. The prison priest who had performed last rites on Diaz earlier in the day said afterward that he’d never seen anyone better prepared to die.

Diaz’s wrists were placed in restraints and he was walked out of his cell to the death chamber less than 20 feet away. “I told you it was only going to be a short distance from the cell to the gurney,” Bryant recalled telling Diaz. “Don’t worry about being weak or whatever -- we [are] going to help you walk over there and I’m going to stay with you through the whole time.”

Don’t worry about being weak or whatever. ... I’m going to stay with you through the whole time.

-----Warden Randall Bryant to Angel Diaz as he walked down death row.

Outside the death chamber, officers guided Diaz onto the gurney. They fastened restraints on his ankles and his legs. Diaz was told to lie down. Bryant thought that he might have touched the inmate's shoulder to reassure him.

Diaz’s arms were placed along the sides of the gurney and restrained. The execution team connected him to a heart monitor and checked to make sure it was receiving the signal. The team then placed a restraint across the inmate’s chest. An IV line was put into one of his arms. “It’s not rocket science,” the warden thought.

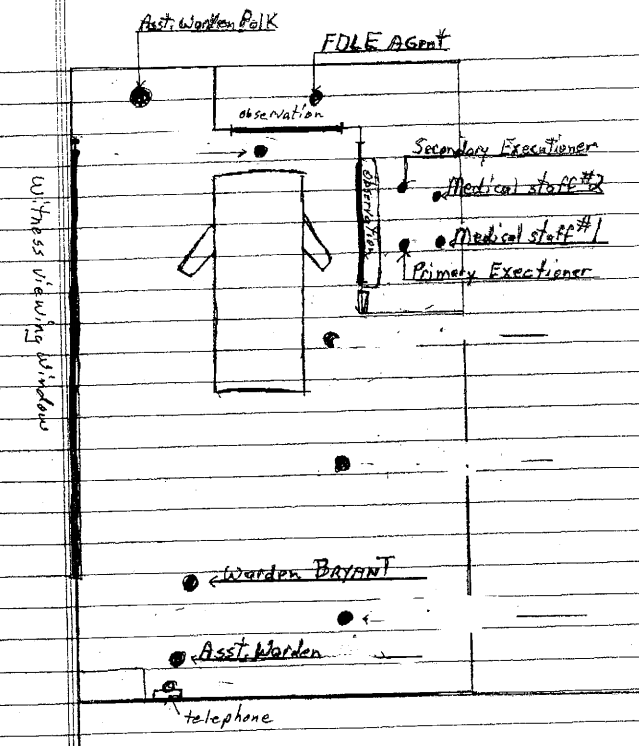

The first drips from the IV contained a harmless saline solution. Officers wheeled Diaz into the death chamber. Bryant checked with the governor’s office to see if there was a last-minute stay. There wasn't. The curtain was opened and the warden stepped to the foot of the gurney, almost touching Diaz’s feet. The warden looked at the prisoner and asked if he wanted to make a statement. Diaz, speaking in Spanish, declared his innocence one last time.

Bryant signaled his team to begin the lethal injection. It was a minute or two after 6 p.m. The execution was now in the hands of the medical personnel. All Bryant had to do was sit in the chamber and wait for Diaz to die.

A thin plywood wall separated the death chamber from the anonymous executioners, who wore what one law enforcement observer later described as “blue moon-suits" with identity-concealing hoods. The medical personnel moved quietly. The room was silent except for the sound of empty syringes being dropped into biohazard waste bins. At Diaz’s side, officers stood rigid and solemn, looking straight ahead or straight down. They were told to display no extra movement. To the gallery witnesses observing through a window, the execution must appear routine, even dull.

Dale Recinella, a volunteer Catholic corrections chaplain who had ministered to Diaz for years, had taken a seat in front of the window. In court testimony and an interview with The Huffington Post, he said he could see most of Diaz's body. A few minutes into the execution, he noticed that the inmate was still blinking and that his throat was still moving. Diaz was alive -- and awake.

“Something’s wrong,” the chaplain whispered.

It looked like Diaz was trying to speak, Recinella recalled. There were stress lines in Diaz’s cheeks and throat. “Then he began to show signs of his body arching,” Recinella would later explain in court testimony. “His body, his torso was arching and it seemed as though it was an involuntary reaction.”

At one point, Diaz moved his head so much that the strap across his forehead slipped. An officer pushed it back in place. Neal Dupree, one of Diaz’s attorneys, was in the gallery. He recalled in an affidavit that his client looked to be in pain. Dupree testified further that Diaz seemed to be trying to speak to the officers inside the chamber. “Mr. Diaz appeared to be gasping for air for at least 10-12 minutes,” the lawyer stated, adding that he saw additional gasps and movement from Diaz for roughly a half hour in total.

Bryant and the people in the blue moon-suits didn't know it, but the intravenous line had ruptured Diaz’s veins in both arms. The lethal chemicals pooled in his arms, severely burning him from the inside. The execution team continued to push more poison into the IV drip.

Most executions don't take more than 12 minutes. Fifteen minutes into his execution, Diaz was still alive. The phone rang inside the death chamber. Bryant picked it up. Gov. Bush's office was on the line.

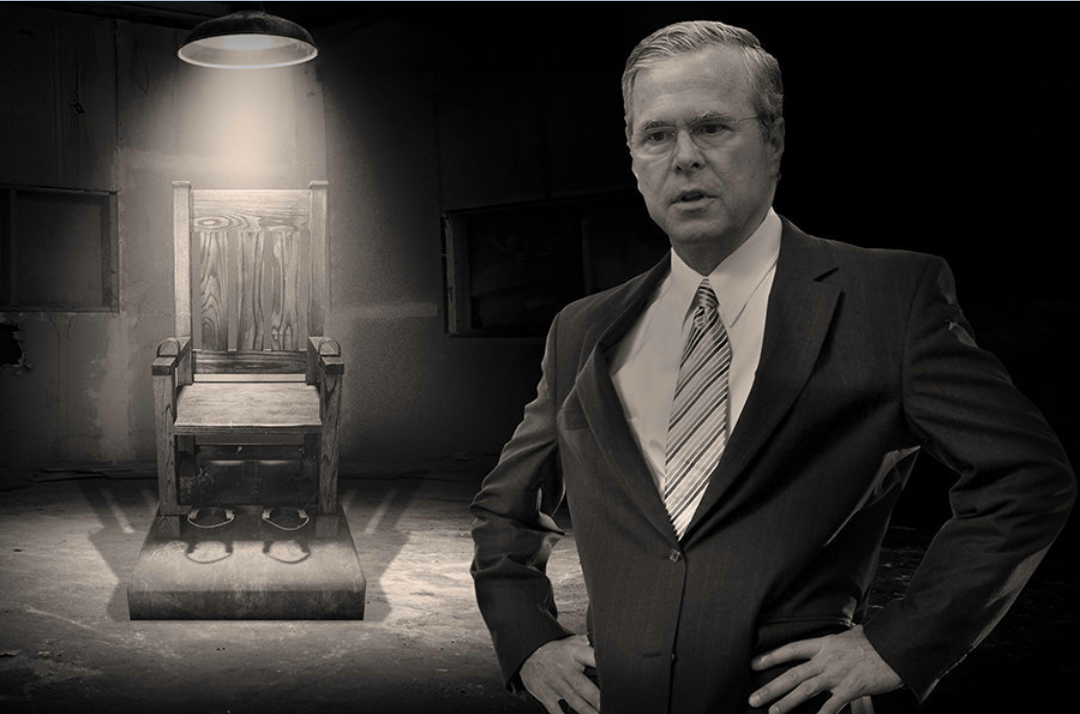

For much of his political career, Bush had said he was conflicted on the death penalty -- a claim he continues to make as he runs for president today. He created the impression that he understood the shortcomings of Florida's capital punishment system, while simultaneously pursuing reforms that exacerbated the system's weaknesses. The Diaz execution would trigger a political crisis that tested whether he could continue this balancing act.

Bush instructed a member of his legal team to call the warden to find out why Diaz was taking so long to die, according to an administration official who was in the room with the governor.

"They were anxious," Bryant recalled.

Florida's history is defined by its endless shoreline, its college football rivalries and its appreciation for killing as spectacle. The state’s long, racist relationship with public killings began well before the bacchanals along South Beach and kickoffs at the Orange Bowl.

Between 1880 and 1940, the period when lynchings peaked in 12 Southern states, Floridians lynched the most African-Americans per capita, according to a 2015 report by the Equal Justice Initiative, a Montgomery, Alabama-based nonprofit.

“Executions occur most frequently in states that had the highest number of lynchings," explained Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. "And historically, the counties that had the highest number of lynchings also tend to be the counties that have the highest number of death sentences and executions.”

The death penalty used to mean death by public hanging. Florida kept hanging people until 1923, nearly a century after Rhode Island became the first state to abolish the gruesome spectacles.

Around that time, according to state lore, prison officials ordered inmates to cut down an oak tree to construct the state’s first electric chair, a structure that would become known as "Old Sparky." By the early 1960s, Old Sparky had been used to kill nearly 200 people.

Then, in 1972, the Supreme Court put a moratorium on capital punishment across the country, ruling in Furman v. Georgia that the death penalty as then applied violated constitutional protections. Lawmakers in the Sunshine State hastily convened a three-day special session to come up with a new system. The complex, multi-layer legal review for death sentences they passed was the first legislative response to Furman in the nation.

The Supreme Court upheld Florida's new death penalty regime in 1976. Three years later, the electric chair was turned back on, and Florida inmate John Spenkelink became the first person in the nation to be involuntarily executed in the post-Furman era. Spenkelink had been convicted of murdering a small-time criminal but maintained his innocence. Presaging future troubles with the death penalty, his execution was shrouded in controversy after officials kept the blinds closed, preventing the public witnesses from seeing the sight.

Still, after Spenkelink's death, Gov. Bob Graham (D), then in his first year in office, saw his popularity rise. Early in his tenure, Graham pursued reforms to make the death penalty more efficient. He established a special counsel in the governor’s office to oversee capital punishment cases and started signing death warrants earlier in an inmate's appeals process to prevent convicts from using the legal system as a stalling tactic.

"If you were taking a poll in Florida, I’m certain it would have been a majority of the public for the continuation of the death penalty," Graham told HuffPost. He was right. One poll in the early '80s showed support for the death penalty near 90 percent.

During the same decade, Florida led the country in the number of people sentenced to death. As of May 1, 1985, “almost one out of every six persons condemned to die in the United States" lived in Florida, wrote Michael Radelet, who researched the state’s death penalty when he served on the faculty at the University of Florida.

Florida's broad sentencing laws helped swell its death row population. It was -- and remains -- the only state in which a simple majority of the jury is enough to recommend a death sentence, meaning that the judge may condemn a defendant to death after a 7-5 recommendation by the jury (Diaz was given a death sentence on an 8-4 vote). It’s also the only state that permits a death sentence without requiring jurors to unanimously agree to the presence of statutorily defined aggravating circumstances. The issue of jury unanimity under Florida law is currently before the U.S. Supreme Court.

The state is one of very few that allow judges to sentence a defendant to death in cases where the jury recommended life in prison. From 1972 through 1999, there were 166 cases in which Florida judges sentenced defendants to death after a jury recommended life, according to Radelet's research.

We are run by Alabama people. We are run by redneck motherfuckers. We are run by those assholes in Tallahassee.

-----Defense attorney Hilliard Moldof

There has been a carnival-like element to executions in Florida. Since prison officials often didn't want to pull the switch, the legislature passed a law to pay $150 to anonymous executioners. Vomit bags were occasionally handed out to witnesses. When lawmakers passed a mandatory seat belt law in 1986, Floridians placed bumper stickers on their cars reading: "I'll buckle up when Bundy does." "Bundy" referred to Ted, the notorious serial killer who had been sitting on death row since 1979.

During the 1986 gubernatorial campaign, one candidate demanded that the state Supreme Court start "burning the midnight oil" to plow through the appeals backlog. Another promised to personally "pull the switch" if elected. Tampa Mayor Bob Martinez pledged that if he was elected governor, "Florida's electric bill will go up." He won.

In 1990, Martinez oversaw the execution of convicted cop killer Jesse Tafero, whose head caught on fire and whose body convulsed in a cloud of smoke and ash as he fried in the electric chair. He was shocked three times over the course of seven minutes. According to the medical examiner, Tafero did not die instantly; in fact, it took him six or seven minutes. Witnesses recalled 6-inch and 12-inch flames shooting from his head. Another witness described seeing the body after the execution: The entire top of Tafero’s head was "covered with wounds," and his eyebrows, eyelashes and facial hair had been burned off. Prison authorities would later blame the gory scene on a synthetic sponge they had used in place of the usual natural one. (Years later, evidence emerged suggesting that one of Tafero's accomplices was the actual shooter.)

Near the end of Martinez's single term as governor, the Florida Supreme Court established a commission to look at racial bias in the criminal justice system. Its 1990-91 report found that people of color were racially profiled and “too often” were victims of police brutality. The commission also reported that people of color were underrepresented in all areas of the legal system, from the cops on the beat to the judges on the bench. African-Americans and Hispanics made up just 8.7 percent and 5.6 percent, respectively, of all law enforcement officers. Juries did not reflect the race and ethnicity of the communities they were drawn from.

For similar homicides, Florida defendants were 3.4 times more likely to receive the death penalty if their victim was white than if their victim was black, according to research by Radelet the commission funded.

These biases are baked into Florida’s DNA, said defense attorney Susan Cary. "There’s an incredible culture of violence here. Very politically conservative, very violent. We are the Deep South,” she said. “We are run by Alabama people,” said defense attorney Hilliard Moldof. “We are run by redneck motherfuckers. We are run by those assholes in Tallahassee.”

In the second half of the 20th century, the racism that had fueled decades of lynchings hid behind a badge and within the jury box. But it endured and, along with a political system that rewarded tough-on-crime lawmakers, ensured that the death penalty remained a central part of Florida's identity.

"Florida was the vanguard," said David Von Drehle, who wrote about the state's capital punishment system in Among the Lowest of the Dead: The Culture of Death Row. "Through the ‘80s, it was the leading state for capital punishment. It had the most inmates on death row and most executions. … That’s the milieu in which Jeb got started in political office."

When Bush first ran for governor, in 1994, he mimicked Martinez's fry-'em playbook. He produced a list of 10 death row inmates whose executions he believed had been unnecessarily delayed and spent the closing days of the campaign attacking Democratic incumbent Lawton Chiles for being soft on capital punishment.

During the campaign, Bush proposed limiting death row inmates to just one appeal in state court. (Defendants could still pursue federal appeals.) "I believe the one trial, one appeal will speed the enforcement of the death penalty by two to four years in most death cases," he argued.

In one ad, Bush featured a murdered 10-year-old's mother who accused Chiles of not doing enough to speed the execution of her daughter's killer. The ad began with photos of the beaming girl and then cut to her mother. “Fourteen years ago,” she said, “my daughter rode off to school on her bicycle. She never came back. Her killer is still on death row, and we’re still waiting for justice. We won’t get it from Lawton Chiles, because he’s too liberal on crime.”

The ad backfired. Chiles noted that he had no power over an ongoing court case. "It was a gross distortion," recalled Mark Schlakman, Chiles’ special counsel. "They were just upside-down wrong on it."

Within days, Bush admitted as much. In the closing debate, he was excoriated as a crass opportunist. His poll numbers never recovered.

Chiles won re-election and the executions continued.

On March 25, 1997, another death row inmate, Pedro Medina, caught on fire in the electric chair, with blue and orange flames shooting out from behind his mask. According to court documents, “after the flame went out, more smoke emanated from under the head piece to the extent that the death chamber was filled with smoke.” The court went on to describe Medina’s body as “mutilated.” “Deposits of charred material” and third-degree burns were reported on the top of his head within a “burn ring.” There were also first-degree burns on his face and head “caused by scalding steam.”

Glenn Dickson, Medina’s minister, recalled watching from the chamber. He was so shocked that he couldn't perform the funeral. “He didn’t die instantly,” Dickson said. “It was the most gruesome thing I have ever seen in my life.”

The Florida legislature responded to the execution not by eliminating the electric chair but by passing a law affirming it as the state's sole method of execution. The vote was 36-0 in the Senate and 103-6 in the House.

By the time Bush ran for governor again, in 1998, he was pitching himself as a different man. He had converted to Catholicism in 1995 at the urging of his wife, Columba, and said it had softened his approach to politics in general and the death penalty in particular.

But it was tough to tell how great a conversion he'd undergone. On the campaign trail, Bush claimed to be "conflicted a little by my faith" but not to the point that he would drop his support for capital punishment. He said that if the pope called to ask him to change his position, he'd be "in awe" but not convinced. "The church does allow for capital punishment in the most heinous of capital crimes," Bush explained.

Sally Bradshaw, Bush's campaign manager in 1994 and 1998, called it "an evolution in message delivery."

Still, when Bush won, his victory gave death penalty foes a sliver of hope that a rising-star Republican governor might become an ally in the cause.

“I believe that, as a thoughtful person and a good Catholic, he was terribly conflicted,” said Talbot D’Alemberte, then president of Florida State University and an opponent of capital punishment who emailed with Bush on the topic. “I had hopes that he would leave the dark side.”

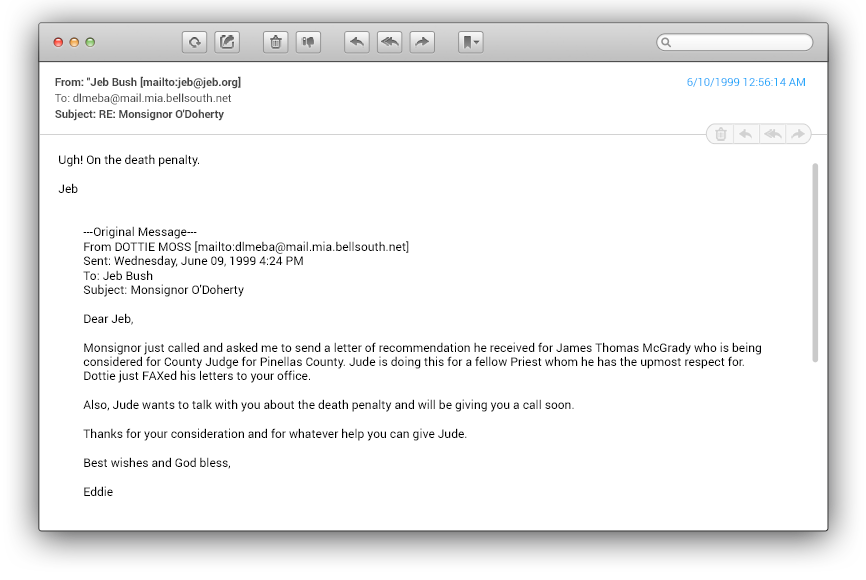

D’Alemberte and others of his ilk were mistaken. In emails, Bush more often expressed impatience than empathy with those who questioned how his faith was compatible with capital punishment. In one email, he rationalized his position by arguing that executions happened “rarely” in the state. In another, he lamented a “double standard that exists in public life. Catholics, it seems get greater scrutiny, than folks of other faith.” In yet another, Bush complained of the church's lobbying on the subject. On June 10, 1999, aides wrote to tell him that a local monsignor wanted to talk. “Ugh! On the death penalty,” he responded.

In a recent interview with The Huffington Post, Bush recalled breakfast meetings with Catholic bishops at which the issue would come up. “The last thing they always talked about -- after feeding the poor, and dealing with homelessness, and giving parents school choice, and protecting the lives of unborn babies -- was the death penalty,” he said. “It is a tenet of my faith and there was a conflict there."

In July of his first year in office, Bush oversaw his first execution.

Allen Lee "Tiny" Davis had been convicted of brutally killing a pregnant woman and her two daughters. He spent 17 years on death row, exhausting appeals and receiving stays from two earlier dates with the electric chair. During his entire time on death row, Davis' weight concerned officials. As his execution neared, it became an urgent matter. The electric chair had a 350-pound limit. Davis came in at 349. The prison put him on a diet and spent $706 for red oak lumber to build a new chair that was wider and less rickety. The electrical current remained the same.

On the day of his execution, July 8, 1999, an arthritic, 344-pound Davis had to be wheeled to the chair by his guards.

At approximately 7:01 a.m., leather belts were strapped around his arms, chest and legs and a 5-inch-wide leather strap was placed across his mouth, forcing his nose upward. A mask was then lowered over his face.

Witnesses said that at this point Davis began issuing muffled screams or moans. When the switch was flipped, blood started to drip from under the mask, over his chin and neck, forming an 8-by-12 inch puddle on his white button-down shirt. Then-state Sen. Ginny Brown-Waite (R) claimed to see the shape of a cross in the blood -- a sign of God forgiving Davis for his sins. Brown-Waite, who was in the room, recalled the execution as "pretty gruesome,” but just.

Davis' muffled screams quieted. But he still appeared to be breathing. After the electrical current was switched off, his chest rose and fell 10 times.

“It took a few moments, seconds really, to realize what was going on, that this was not the normal, quiet, efficient execution that the state wanted portray,” said veteran Tampa reporter John Sugg, who also witnessed the execution in person. “He wasn’t dead. You could hear him. I heard him.”

By 7:15 a.m., Davis has been declared dead. His body was covered in burns -- on his head, his groin, and behind his right knee. Photos taken shortly after showed his face had turned purple, likely the result of partial asphyxiation.

Bush was unapologetic. In the days after the execution, he insisted, as prison officials would too, that the bleeding started before the electricity, and he pleaded that sympathy be directed toward Davis’ victims. The controversy, he said, was “an argument over a nosebleed.”

Following the Davis execution, another death row inmate challenged the state's use of the electric chair. In September 1999, the Florida Supreme Court ruled, 4-3, that the chair was legal. In a scathing dissent, Justice Leander Shaw wrote that Davis was “brutally tortured to death by the citizens of Florida” and described the state’s record of bungled executions as “acts more befitting a violent murderer than a civilized state.” To make his point, he included photos of Davis’ body in his dissent.

"Execution by electrocution -- with its attendant smoke and flames and blood and screams -- is a spectacle whose time has passed," Shaw wrote.

The sorry state of the death penalty in Florida was on the mind of Stephen Hanlon, then the partner in charge of Holland & Knight’s pro bono department, when he spotted Bush in the law firm’s Tallahassee office shortly before Bush took office. He knew what he needed to do. He dug out his copy of Von Drehle’s book and handed it to Bush.

The book detailed what Hanlon knew all too well: Florida struggled to find and fund qualified lawyers to defend the condemned and qualified judges to oversee the trials. The judicial system, as Von Drehle wrote, was “a slapdash machine designed in confusion, built of spare parts and baling wire.”

Between 1973 and 1995, the Florida Supreme Court reversed 49 percent of the state’s death sentences after analyzing trial transcripts and finding errors, a 2000 Columbia University study found. That count didn't include inmates who were freed based on new evidence, faulty witness testimony, or coerced confessions. Florida led the country in death-row exonerations during this period.

Hanlon had worked death penalty cases and knew how overburdened appellate lawyers were. He needed Bush to know that the system was hitting a crisis point. “This is the brain surgery of our profession,” he said, “and we were throwing people at it who just had no idea what they were doing."

At some point early in his first year in office, Bush returned to Hanlon’s office with the Von Drehle book full of passages underlined in red ink. In their conversation, Bush acknowledged that there were problems with defense lawyers and questions about whether the death penalty even deterred crime, according to Hanlon.

“My general impression was this was a very smart guy,” Hanlon said. “He was very much into policy. He knew there were very serious problems.”

I believe that, as a thoughtful person and a good Catholic, he was terribly conflicted. ... I had hopes that he would leave the dark side.

-----Talbot D’Alemberte, then president of Florida State University.

But Bush and his staff didn’t see a broken system. They saw instead an activist Florida Supreme Court that gummed up the appeals process and needlessly prevented executions from taking place. Writing for the conservative Federalist Society for Law and Public Policy Studies newsletter in August 1999, Reginald Brown, Bush’s then-deputy general counsel, lamented the high percentage of death sentences the court reversed -- at that point, 79 percent.

“Jeb believed in the death penalty and wanted to enforce it,” Brown told HuffPost. “He thought that the Florida Supreme Court was trying to do a pocket veto of the law.”

In October 1999, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to take up a case from Florida asking whether the electric chair amounted to cruel and unusual punishment. Two months later, Bush called a special session of the state legislature and pushed a bill that designated lethal injection as the main method of carrying out executions while leaving the chair as an option. The bill quickly passed through the legislature. The threat of a U.S. Supreme Court decision gutting Florida's death penalty was averted.

During the same special session, Bush called for legislation to severely limit the ability of death row inmates to appeal their sentences. He and his allies promised that the bill, known as the Death Penalty Reform Act of 2000, would reduce the average time between sentence and execution from 14 years to five years or less. "What I hope is that we become like Texas: Bring in the witnesses, put them on a gurney, and let’s rock and roll," Bradford Thomas, Bush's top adviser on the death penalty, chest-thumped to the St. Petersburg Times. (Bush would later appoint Thomas as an appellate judge.)

Raquel Rodriguez, Bush's former general counsel, told HuffPost that the governor "felt the system was being abused and that those delays were an abuse of the system and a disservice to the victims, who were forced to live for years and years knowing that the person who killed their loved one was still sitting in prison even though they had been sentenced to death."

But members of the state legislature's black caucus objected strenuously, even inviting Freddie Pitts, one of the state's most famous exonerees, to testify. Pitts and another man, Wilbert Lee, had been wrongly convicted of the murder of two gas station attendants in 1963 after police beat them into confessing to the crime. Pitts recalled to HuffPost that the sheriff at the time bragged, “This will be two niggers that won’t be in that March to Washington.”

Pitts said he and Lee were pressured to plead guilty. An all-white jury sentenced them to death. The entire proceeding took less than a day. They remained behind bars even after a white man confessed to the murders. They would not be exonerated until 1975.

A quarter-century later, Pitts addressed the Florida House of Representatives. Republicans had allowed him only one minute to speak, he said. He explained that had Bush’s law been in effect when he was on death row, he would be dead. Then he walked off the floor.

“It was dead silence for a good minute, maybe longer,” Pitts remembered.

It wasn't enough. The bill passed by a single vote after the second-ranking House Democrat defected to back the measure.

Bush heralded the bill as “a historic piece of legislation” that would be "respectful of family members and victims" and “bring a semblance of justice to this very complicated issue.”

Others were shocked. “It just doesn’t make any sense for a guy who was that bright,” Hanlon said. “The one word I would use is inexplicable. That wasn’t the Jeb Bush I thought I knew.”

The Florida Supreme Court had another word for the legislation: unconstitutional. A few months after the governor signed the bill into law, the court ruled that it violated the state constitution’s separation-of-powers clause and the rights of defendants to due process and equal protection. The court voided most of the new statute, but warned that the capital punishment system's problems would endure unless the state provided proper funding "for competent counsel during trial, appellate, and postconviction proceedings."

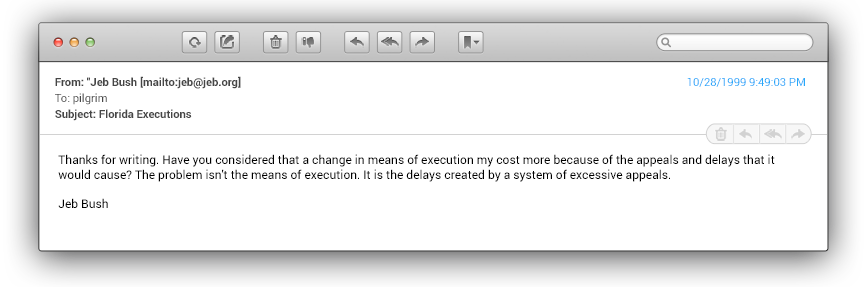

Bush was unbowed. In his short time in office, he had already seen a botched execution and legal setbacks with the state Supreme Court rebuke, yet he pressed forward. “The problem isn't the means of execution," he wrote in one email. "It is the delays created by a system of excessive appeals.”

As Bush attempted to hasten death row appeals, he sought to calm critics by setting up a task force to analyze whether race played a factor in the state’s capital cases. For those familiar with the death penalty in Florida, it was entirely redundant.

“You didn’t need a task force to know looking at the simple numbers that the race of the victim played a major role, especially in Florida,” said state Sen. Chris Smith (D). “The dirty little secret in politics is the task force was only set up to muddy the waters."

Ultimately, Bush’s task force recommended that the issue of race be studied further. Neither the governor nor the legislature established an initiative or set aside funding to examine the issue again. Instead, executions in Florida continued without pause.

The one word I would use is inexplicable. That wasn’t the Jeb Bush I thought I knew.

-----Stephen Hanlon, former partner in charge of Holland & Knight’s pro bono department.

On June 7, 2000, Bennie Demps, a racial justice advocate within the prison system, was put to death by lethal injection. Demps had been convicted of killing a fellow prisoner. He never stopped professing his innocence, claiming he had been set up by corrupt officials. Before his execution took place, Pope John Paul II sent a letter to Bush seeking clemency. The governor declined to grant it.

The execution went awry shortly after it began. Technicians struggled for more than a half-hour to find a vein. When the curtains in the chamber finally opened, Demps screamed out that what was about to transpire was nothing more than a "low-tech lynching."

In a narrative of events he wrote after the fact, George Schaefer, one of Demps' attorneys, recalled the anxiety building in the witness gallery during the delay and remembered hearing “some strange drum beats or perhaps even music while waiting.” That anxiety turned to shock once Demps appeared and delivered his last words. Schaefer wrote that his client “went on to ask that I request an investigation of what had just happened to him. He said that the officials had cut into his groin and into his leg and that he had bled profusely. He said that it was very important that his body be examined because it would show where there were sutures. He mentioned he had been ‘butchered.’”

Schaefer had nightmares for a month after the execution, he said. He eventually moved to San Diego, where he currently works as a lawyer for the city handling civil litigation. “It was very traumatic for me,” he said.

At the governor's office, there was a different reaction. Asked for his thoughts after the Demps execution, Bush replied that the procedure was done "according to the textbook."

"There was no botched nature to it at all."

In December 2000, shortly after Vice President Al Gore conceded the presidential election to then-Texas Gov. George W. Bush, and with the country still debating hanging chads, Barry Scheck found out that DNA tests proved his client Frank Lee Smith had not been guilty of capital murder. The famed defense attorney heard the news while he was in his New York office. No Florida official called him. The information was leaked to the media.

Scheck suspected that the leak was timed to ensure the embarrassing news was buried.

“It just seemed like such a waste,” said Scheck, who co-founded the Innocence Project in the early ‘90s. “They fought us for so long, and it was so absurd that we couldn’t get these tests.”

Smith didn't live to celebrate his freedom. He had died on death row a year prior.

Smith never caught a break when he was alive, either. He grew up in stifling poverty and lived a life full of trauma, according to Frontline’s reporting on his life and case. His father had been shot and killed by the police. His mother worked as a prostitute. He bounced from foster care to a corrupt and brutal reformatory to prison stints. His last days were spent in agony.

In 1985, Smith was convicted of the rape and murder of an 8-year-old girl. On death row, he continued to proclaim his innocence. The court dismissed his appeals even after the key witness in the case recanted her testimony. A judge denied a motion to test the DNA evidence in 1998.

While on death row, Smith was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Martin McClain, one of the many attorneys who worked on Smith’s appeals, recalled meeting him before a hearing. Smith had drawn what looked like a crossword puzzle. But only gibberish filled the boxes. Smith showed him the diagram and said it proved an ancestral link between him and the judge.

“Trying to understand any of the conversation with him was virtually impossible,” McClain recalled. “He wasn’t grounded in the real world.”

Confined to a bed and denied pain medications, Smith succumbed to cancer on death row in January 2000, before a judge granted DNA testing. Even then, prosecutors tried to block the test.

Sixteen months after Smith’s death, and after another Florida inmate with severe mental disabilities was exonerated by DNA evidence after serving nearly 22 years of his life sentence, Bush signed into law a bill that gave death row inmates and others an avenue to obtain testing of DNA evidence. But there was a catch: Inmates were severely limited in when and how they could request that a test be run.

“I think they made some errors in trying to be too restrictive in that statute,” Scheck said.

Sometimes in life you do things even though you are conflicted. It is not always black or white. It is not always either/or.

-----Jeb Bush on the death penalty.

Still, Bush recognized the importance of bringing additional evidence into the legal process. In one case, he granted a last-minute stay for a death row inmate after Scheck flew to Tallahassee to make a personal appeal for a DNA test. Scheck said he got a call from Bush with news of the stay while waiting for his return flight. “Next time, don’t wait so long,” Bush told him.

Bush sought to reform the death penalty process in other ways as well. Weeks before he signed the bill for additional DNA testing, he approved legislation that barred the execution of mentally challenged inmates. He told HuffPost that as governor, he would bring the state psychologists into his office to discuss individual cases where the death row inmate might have a borderline IQ. And he insisted that when the person's mental capacity was questionable, he "didn't sign the death warrant."

Bush and his advisers look back now and argue that these reforms show a governor adaptive in his politics even as he remained committed to certain beliefs.

"Sometimes in life you do things even though you are conflicted. It is not always black or white. It is not always either/or," he told HuffPost. "Sometimes there are principles and values on both sides that you can respect."

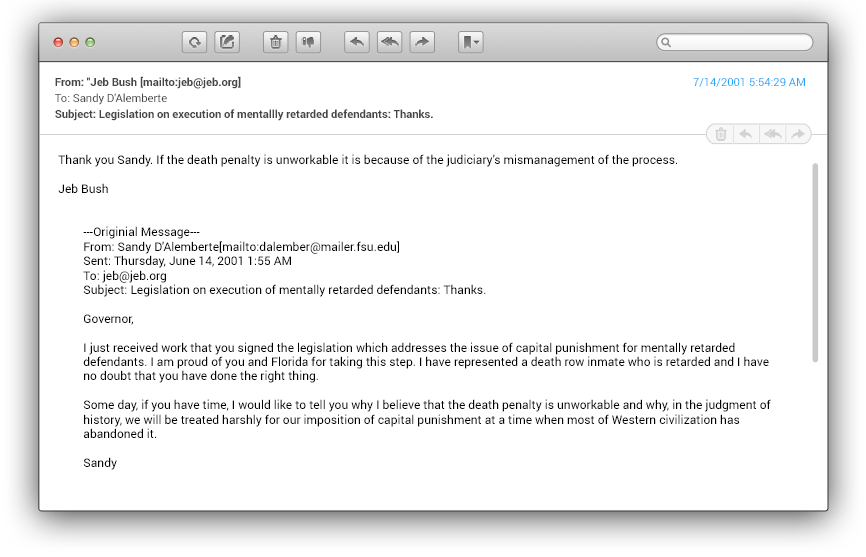

But the changes he pursued in Florida came too late for Frank Lee Smith. And, in truth, they were marginal. Bush still believed that death row appeals needed to be sped up. When D’Alemberte emailed on June 14, 2001, to thank Bush for signing legislation ending executions of the mentally challenged and to encourage him to end capital punishment entirely, Bush responded coldly.

“If the death penalty is unworkable it is because of the judiciary’s mismanagement of the process,” he wrote.

And yet, that judiciary continued freeing people from death row.

In January 2002, Juan Roberto Melendez was released from prison after spending 17 years on death row. His trial, in which he was accused of killing a white beauty salon owner, had lasted all of one week: two days for jury selection, one day to hear the case, one day for the jury to decide his guilt, and the last day to sentence him to death. The foreman had convinced a holdout juror to convict after highlighting the size of Melendez’s afro.

Melendez was innocent. Even before his trial, another man had confessed to authorities. But it wasn’t until the confession and other inconsistencies in the prosecution’s case were revealed in Melendez's fourth appeal that he was freed.

Melendez left prison with $100, a pair of pants, a T-shirt and a case of post-traumatic stress disorder. “In the end, I didn’t care if they killed me or didn’t kill me. I was thinking whatever they are going to do, they are going to do anyway,” he told HuffPost. “The people who worried about it went crazy.”

A year after Melendez was released, Rudolph Holton left death row, too. He had been imprisoned for 16 years before the courts determined that the evidence was insufficient to retry him for the murder of a Tampa teen. It was the fourth time in Bush’s tenure as governor that a Florida inmate had been exonerated while on death row and the 23rd time since 1973. Florida continued to lead the nation in death row exonerations. Those who worked with Bush say that the systemic miscarriages of justice, combined with the sloppiness of several executions, began affecting the governor.

"He was very somber about it. He prayed on it. It was definitely not something he took lightly," said Rodriguez, his former counsel.

"[T]he longer he was in, the softer he became,” said state Sen. Victor Crist (R), who helped craft the appeals reform bill that Bush pushed in 2000. “With time, he got past the politics and the rhetoric. He is a thinker. He is nothing like his brother.”

But Bush never backed away from capital punishment. In fact, as he ran for a second term in office, he saw it as a political asset.

Bush's 2002 campaign emphasized the protections he had put in place for the mentally challenged and the expansion of DNA testing. But it also stressed his strong support for the death penalty and his continued commitment to ensuring "that capital cases are resolved within five years."

That summer, the state Republican Party ran ads criticizing the top two Democratic candidates for governor for doing a "song and dance" on various issues, including the death penalty. And as the state Supreme Court began hearing arguments as to whether a recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling on the death penalty would impact Florida, Bush plowed forward as if there were no legal issue at all. In early September, he signed the death warrants for two more inmates.

"This is a transparent and crass political move," Abe Bonowitz, then director of Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, said at the time.

It took until late October for the state Supreme Court to finally rule that Florida's system was not affected by the U.S. Supreme Court ruling. A few weeks later, Bush won re-election. Soon after, he set the execution dates for the two inmates whose warrants he had signed.

By that point, however, Bush had already set his sights on a new objective: the privatization of the state agency responsible for helping potentially innocent men get out of prison.

Bush's target was the Capital Collateral Regional Counsel, a government agency established in the mid ‘80s to give defendants on death row legal representation in their appeals.

The agency was born out of the Florida Supreme Court's concern that there were inmates with execution dates who did not have counsel.

Despite persistent funding problems and heavy caseloads, the CCRC attorneys proved to be strong advocates for their clients. By the end of Bush’s first term, the agency's lawyers had helped dozens of inmates, including Melendez and Holton, get their convictions tossed out or their death sentences reduced.

In January 2003, Bush proposed eliminating the CCRC and replacing it with a private registry of attorneys. The attorneys would be paid only after they finished various motions and pleadings, giving them an incentive to work faster.

“He was trying to ensure that lawyers like myself would not succeed in challenging the death sentences,” said McClain, who represented Smith and Melendez. “After the creation of CCRC, the lawyers actually did stuff, won cases, etc.,” McClain added. “Florida had been leading the nation in executions when CCRC was created. It wasn’t anymore.”

The governor didn’t try to argue that abolishing the CCRC would lead to better lawyering. Instead, he sold it as a means of achieving his long-elusive goal of expediting the appeals process. His administration promised that closing the CCRC would result in "death sentences [that] can and should be resolved within five years, not 15 to 20 years."

Bush also argued that taxpayers could save a few million dollars annually by closing the CCRC. It was a meager budget gain for the state, and apparently not enough to persuade the legislature to go along with the proposal. In May 2003, a compromise was reached: Only the CCRC’s northern office -- the same office that had freed Melendez and Holton the year before -- would be replaced with private lawyers.

[T]he longer he was in, the softer he became. With time, he got past the politics and the rhetoric. He is a thinker. He is nothing like his brother. State Sen.

-----Victor Crist (R) on Jeb Bush's approach to the death penalty.

Bush wasn't done. The next year, he tried to close the remaining two offices, according to state Sen. Crist. This time officials in the Catholic Church, worried that Bush's plan would severely disadvantage defendants and potentially endanger innocent people, dissuaded him from pushing forward, Crist said.

Those officials had reason to fret. Many of the attorneys in the registry proved incapable of handling death penalty appeals, which can be incredibly complex. McClain recalled taking over a case from one lawyer who told him that he refused to visit his client and thought the inmate deserved to be on death row. Other registry attorneys failed to file federal appeals on time.

Florida’s top judges also took notice. In 2005, Florida Supreme Court Justice Raoul Cantero, a Bush appointee, called the casework filed by some of the registry attorneys “the worst lawyering I’ve seen” and “the worst briefs that I have read.”

In January 2007, the month that Bush left office, the state’s auditor issued its own report comparing the CCRC with the private registry system. It found that registry attorneys spent on average 196 hours per case while the CCRC lawyers averaged 355 hours per case. In fiscal year 2004-05, the private registry interviewed 13.4 witnesses or experts per case while the CCRC interviewed roughly 32 per case. During the same time period, and with nearly the same caseloads, the CCRC had 105 cases in which lawyers filed public records requests while the registry had just 15.

Even Bush’s conservative brethren in the legislature deemed the experiment a failure. "He thought we could get greater efficiencies out of the privatization," explained Crist, a critic of the idea. "But it ended up being primarily people doing it for the money and not the cause. The courts were telling us they could lose faith in the process. ... And if you believe in the death penalty, you can't risk the courts losing faith in the process."

The biggest change Bush had made to Florida's already troubled system of capital punishment had made it even less functional.

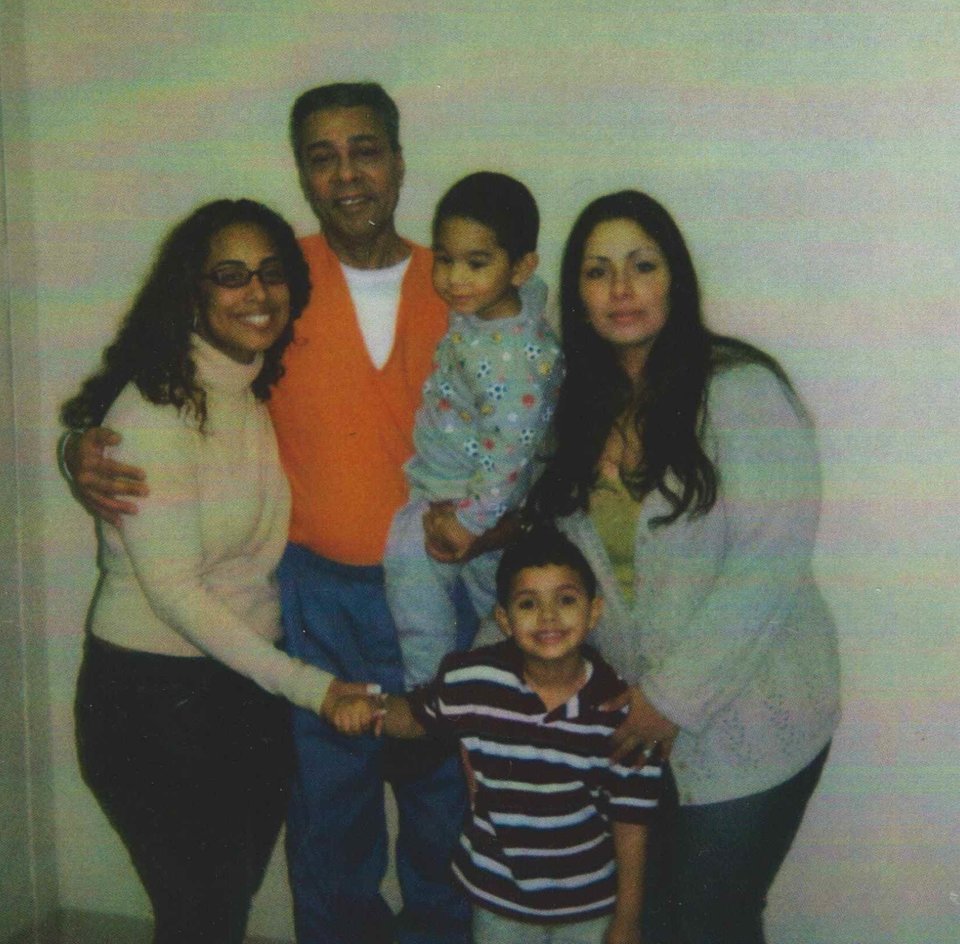

On the morning of Angel Diaz’s execution, his family came to see him one last time. There would be no more court hearings, prison phone calls and visits separated by glass. The mood was somber. Diaz tried to focus on the future, his family’s future. He didn’t want his execution to eat away at them. “He told me that I was a daughter to him,” said Maria Otero, a second cousin. “He asked me to always keep the family together.”

After Diaz was escorted back to his cell, the family asked Recinella, the volunteer chaplain, if they could take Communion. They found an empty room and gathered in a circle, then held hands and recited the Lord’s Prayer as corrections officers stood watch. During the short service, they prayed for the officers and staff who would be taking part in the execution.

Hours later, the family gathered at a designated area outside the prison. Soon, what sounded like a horn or a bell rang from the prison, letting the crowd know it was 6 p.m. -- time for the execution. All the family could do was wait.

“Your hands are tied,” Otero said. “Your voice cannot be heard. You cannot do anything about it. You are just standing there not knowing what was happening.”

At the governor's office, Bush gathered with top staff. Earlier, his lawyer had placed a call to Charlie Crist, then the state's Republican attorney general, to confirm that Diaz had no outstanding appeals. Now, they were on the phone with the prison warden trying to figure out what was taking so long. Officials at the prison said that nothing was amiss. But as the minutes passed, Bush became convinced otherwise. Diaz was "snoring" but "still unconscious," the governor's office was told. More minutes passed.

Finally, James McDonough, the secretary of the Florida Department of Corrections, asked George Sapp, a trusted corrections administrator, to go to the death chamber to find out what was happening. Sapp walked to the edge of the chamber. With Diaz clearly not yet dead despite the lethal chemical cocktail injected into his body, Sapp began asking questions.

He reported back to McDonough that there were problems with Diaz’s liver and that the team was having a hard time pushing the deadly fluids into his veins. A subsequent investigation would find that Diaz had no liver problems. The execution team had pierced Diaz’s veins and toxic chemicals weren't flowing into his bloodstream. His arms would show chemical burns from the inside. One law enforcement official who saw Diaz immediately after he died noticed a blotchy redness on his arms. “It was an attention getter,” the official said in a court hearing. The lead executioner would later admit that he had never received medical training and had "no qualifications" to administer the drugs.

The team assured Sapp that Diaz’s death was imminent. This also proved false. At 6:24 p.m., Diaz's mouth and chin "slowly stopped moving and his eyes appeared fixed," according to a government timeline of the execution. Two minutes later, his body "suddenly jolted" and his eyes appeared "to be opening more widely."

A supervisor with the Corrections Department’s public relations office tried to call in to the death chamber. Warden Bryant refused to take the call.

Diaz’s execution lasted 34 minutes.

I just watched a man be tortured to death.

------Dale Recinella, Angel Diaz's spiritual adviser.

“It’s death,” McDonough told HuffPost. “It’s never a comfortable sight. People fight for their life just like animals fight for their life.” He added that there’s a false expectation that a lethal injection means a “tranquil death.” “All witnesses to an execution observe things in different ways,” he said. He doesn’t think Diaz really suffered.

Recinella recalled driving home traumatized after the execution. Once he got into cell phone range, he called his wife. She didn’t recognize his voice. “Dale, is this you?” she asked. “What happened?”

“I just watched a man be tortured to death,” he told her.

As with past botched executions, Bush was initially defiant. He blamed the debacle on a "pre-existing medical condition of the inmate" (the alleged liver problem), claimed that the Department of Corrections had followed all the proper protocols, and dismissed calls for a moratorium.

"All the people that are against the death penalty whenever there's a chance will call for suspending the death penalty," he said. "That would be like ready, fire, aim."

But a day later, after receiving the medical examiner's report on Diaz's death, Bush directed Rodriguez, his general counsel, to prepare an executive order establishing a commission on lethal injection.

The next day, he suspended all executions in the state.

By halting executions in Florida, Bush again created the impression that he was acting on his professed uncertainty about the practice. By that point, even his ideological allies had come to believe that he had changed dramatically from the time he had entered office.

"He came in gung ho to crank up Old Sparky and blaze through it," said Crist, the state senator. "But once his hand was on the throttle and his wife had his ear, he began to back away and become far more sympathetic and compassionate and a little less aggressive."

Looking back now, from the presidential campaign trail, Bush said that the "protocols" hadn't been applied correctly in Diaz’s case and that the process "didn't work in the way that" it should have. "It should not be a gruesome procedure," he told HuffPost. "This is a completion of a sentence. Justice delayed is justice denied."

After Diaz’s execution, Bush continued sending emails to those who shared their thoughts about the death penalty with him. In one, he revealed that he was more concerned about the fate of the death penalty itself than with another bungled execution.

“We have to adhere to protocol or the courts will kill the death penalty. That is why we set up this commission," he wrote.

A few months later, after the commission issued its report, the new governor, Charlie Crist, lifted the moratorium, and the death penalty returned to Florida.

Additional reporting by Scott Conroy

- Publish my comments...

- 0 Comments